In thinking about the icy humanities, it is worth considering not only ice, which is fast vanishing, but also our humanity. Let us hope that we do not also lose that, too.

On Tuesday, I gave a few remarks at the Icy Humanities: A Collaborative Symposium hosted online by a number of institutions: Boston University’s Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future, the University of Cambridge’s Scott Polar Research Institute, the International Glaciological Society, and the University of Bristol’s School of Geographical Sciences. The interdisciplinary event was intended to bring social scientists, humanities scholars, and Earth scientists together to discuss ice, past, present, and future. My remarks from the event are below.

***

People often ask me why I study the Arctic when I’m from California. I suppose the answer is that it’s something to which I’ve long felt drawn. Ice didn’t occur naturally in the chilly-but-never-cold-enough city where I grew up, San Francisco. We had to travel long distances to see it, whether that was four blocks to the ice cream parlor, which once felt like an eternity to me, or, when I got a bit older, four hours to the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Frozen water is something I’ve always had to seek out.

At least, ice was something I always could seek out until the COVID-19 pandemic hit. As the world was shutting down, I found myself on top of the last bit of glacial ice I’d see for a long time: Fox Glacier on New Zealand’s South Island. Below me, the iridescent ice descended into the lush green podocarp rainforest fanning out into the temperate Tasman Sea. There was ice, but I definitely wasn’t in the Arctic.

I was in New Zealand with one of my closest friends, a glaciologist who had recently gotten married in a wedding dress dyed to resemble the blue-to-white gradient of an iceberg, and her partner. This was their honeymoon, and a rather well-timed one at that. My motivation for traveling to New Zealand wasn’t so much because I’d gotten hitched, but rather because I was realizing a teenage dream to visit the country I’d held since watching Lord of the Rings in the early 2000s.

If you’ve seen the film, you might remember how some scenes were shot in New Zealand’s Southern Alps, which double for Minas Tirith. At one point in the movie, beacons are lit atop a ridge as a cry for help. Unbeknownst to me when I first watched the movie in 2003, the ice and snow captured in the shots were shedding tears, too.

Not too far from the filming location, one famous hike out to the imperially named Franz Josef Glacier, which the Māori call Kā Roimata ō Hine Hukatere (the tears of Hine Hukatere), now leads to a desolate, dry valley. The only telltale sign of the ice is a matter-of-fact sign: “In 1908, the glacier ended here.”

But even in 2006, a few years after filming on Lord of the Rings wrapped, satellite imagery reveals that the ice was still visible from this point of the trail. It’s only in the past few years that the ice has retreated from view. This shrinking suggests is that, in thinking about the icy humanities and in where we might find archives of icier worlds, we needn’t go back to centuries-old paintings or whaling logbooks. We only need look back to Hollywood blockbusters filmed a mere two decades ago to see a more glaciated past.

Icy imprints in Hong Kong

As the pandemic was racing around the world in March 2020, I hurried back from New Zealand to my home in Hong Kong. For the next 15 months, I was unable to leave the subtropics and thought that I wouldn’t be able to seek out ice. But gradually, I learned to see the fingers of icy worlds extending all around me.

Just blocks from my apartment was the epicenter of the world’s mammoth trade. 80% of Siberian mammoth tusks dug out of the tundra end up in Mainland China after coming through the trading hub of Hong Kong. Diamonds dug out of the same permafrost-laden ground–the crystalline result of an asteroid impact 36 million years ago–are also increasingly wending through Hong Kong’s glitzy shops as Asian demand for luxury goods grows.

There are more historic traces of icy pasts, too. Hong Kong was only rendered “habitable” by the standards of heat-intolerant British colonists as a result of the global ice trade. The Tudor Company shipped blocks of ice that were hand-cut by men out of New England’s frozen lakes, themselves the vestiges of the last Ice Age, by tucking them in between layers of insulating hay on vessels which sailed halfway around the world. Below, you can see an excerpt from a newspaper at the time, expressing, “One can easily imagine the anxiety with which hospitals and even private citizens looked forward to the arrival of these ships.”

This North American ice was imported to Asia until the end of the 1890s. From the docks, Chinese laborers pulled the frozen water up the perilously steep Ice House Street (which also lent itself well to mischievous children looking to slide down on blocks of ice, as one former Hong Kong chief executive remembers from his youth) and into an ice house run by a British company called Dairy Farm. This building not only stored ice, but also other European wares from butter to Siberian fur coats, which would have molded in the absence of cold storage.

Eventually, Dairy Farm would grow into one of Hong Kong’s largest conglomerates. Ironically, it now owns the Hong Kong and Taiwan branches of one of biggest brands in the world from an Arctic country: Sweden’s IKEA. From its shops, you can buy the latest fad polar product: cloudberries. (The former ice house is now the “Fringe Club,” located next to the Foreign Correspondents’ Club.)

The ice trade ended in the late 1800s in Hong Kong, when the recent discovery of ammonia-compression refrigeration techniques arrived on its sweaty shores. Nearly overnight, factories could manufacture artificial ice to cool down the bodies of overheating colonists, while the machines’ emissions turned the “natural” ice at the poles into sorry puddles.

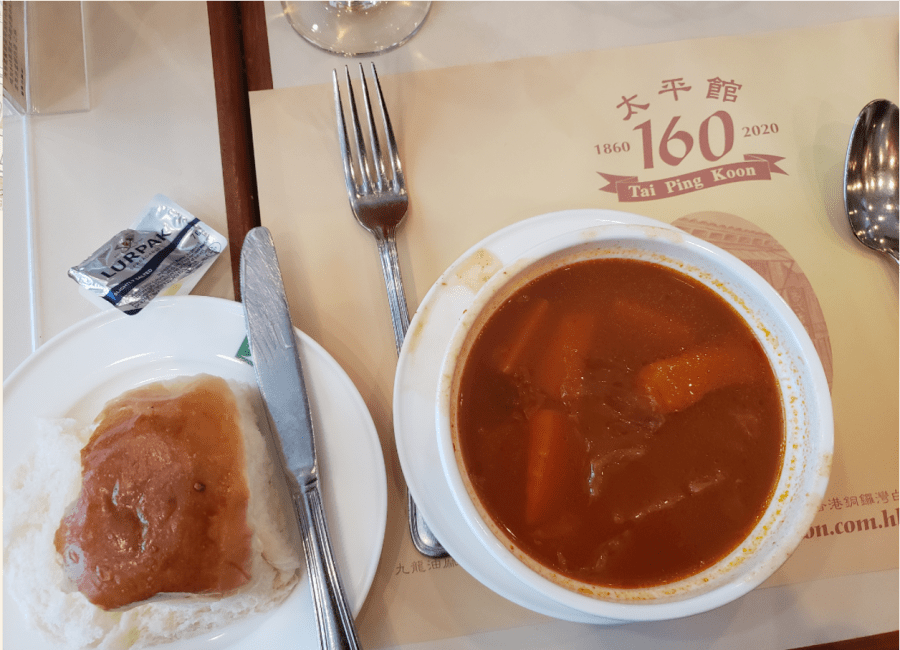

Perhaps the places where I was surprised by the imprint of colder cultures were Hong Kong’s cha chaan tengs. These diner-like restaurants often serve borscht. The hearty beet soup was brought by the thousands of Russian emigres who arrived in Hong Kong in the 1940s and 1950s, having fled the revolution in China. They were refugees twice-over, for most were in China after having fled the Russian Revolution in 1919, settling in cities like Harbin, Beijing, and Shanghai. Forced out from their adopted homes during the Chinese Revolution in 1949, many found their way to Hong Kong, where they started restaurants or bakeries. Coincidentally, Russians in Hong Kong also benefited from the Ice House and Dairy Farm. Many would make special orders for Russian cheese curds (tvorog) for holidays. In the absence of cold temperatures, their traditional foods, too, relied on refrigeration. Back home, their vaunted pelmeni – small Siberian dumplings – used to be buried in ice for preservation.

So, here I was, eating my borscht – which, it should be said, is now a beet-less bastardization of the original – and thought about how these so-called White Russians, due to their anti-communist allegiances during the revolution, had ended up thousands of miles from their homes.

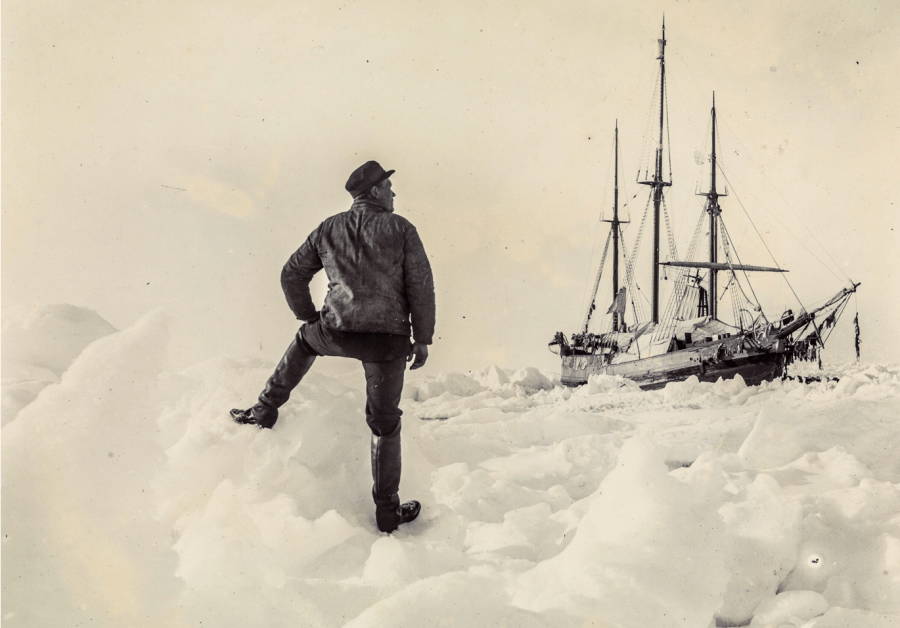

Looking back on this moment through the lens of icy humanities reveals the repetition of cycles from the glaciological to the societal. One individual who played an important role in resettling the millions of people displaced during the tumultuous twentieth century was Fridtjof Nansen, the Norwegian explorer who was the first to cross Greenland on skis. The League of Nations had appointed him as High Commissioner for Russian Refugees in 1921, during the events that first sent White Russians fleeing to China. He invented the “Nansen passport,” which helped give displaced people the documentation they needed to begin a new life somewhere.

A century later, millions of refugees are on the run again, this time as a result of Russian actions in Ukraine. In thinking about the icy humanities, it is worth considering not only ice, which is fast vanishing, but also our humanity. Let us hope that we do not also lose that, too.

Hello Mia,

I just read your last post “Icy humanities: From New Zealand to Hong Kong” and I wanted to tell you what an interesting collection of “icy fingers” you gathered. I read it with great pleasure.

I also wanted to hand you this article from the New Yorker regarding the ice trade from North America, which I found really well-written as well.

-> Owen, David. ‘How the Refrigerator Became an Agent of Climate Catastrophe’. The New Yorker, 15 January 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-a-warming-planet/how-the-refrigerator-became-an-agent-of-climate-catastrophe.

Anyway, thank you for this good read you crafted.

Best wishes, Joaquim (from Sciences Po, Paris)

Thank you, Joaquim! I hadn’t seen this article. Thanks for sharing it – I’m looking forward to reading it.

Cheers,

Mia