Featured image: At last week’s Senate hearing on ANWR, the sartorial choices between the Gwich’in (3rd from left) and Iñupiat (fourth from left) witnesses were clear.

In early November 2017, the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources held a five-hour hearing on drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). Established in 1960 by President Eisenhower, ANWR has witnessed decades of clashes between environmentalists and industry supporters, Alaskans and non-Alaskans, and Juneau and Washington, D.C over proposals to open the refuge to drilling. The crux of the matter is whether to allow petroleum exploration and production in the non-wilderness Area 1002, the coastal plain situated on Alaska’s North Slope that washes into the Arctic Ocean. This area may hold between 5.7 and 16 billion barrels of oil – about 8.7 percent of the United States’ estimated undiscovered, recoverable oil.

While the Obama administration was a staunch protector of ANWR, the Trump administration has proposed lifting restrictions on energy exploration in Alaska. It also is eyeing a potential $1 billion in revenues from ANWR lease sales to help pay for a $1 trillion tax cut. Since Congress needs to approve any exploration in Area 1002, that’s why the Senate was holding a hearing on Thursday, inviting 12 witnesses to testify.

ANWR has a lot more than just oil

There’s a lot more than just oil in the tundra. Approximately 241 people, mostly Iñupiat, live in the village of Kaktovik, the only one in ANWR. The nearly 20-million acre refuge is also home to a rich array of wildlife including polar bears, Dall sheep, and, notably, the Porcupine Caribou herd. The Gwich’in people, who reside in 15 small villages stretching from northern Alaska to northwest Canada, rely on the caribou for their subsistence way of life. Many Gwich’in are deeply worried that oil exploration in Area 1002 would irreversibly impact the caribou’s calving grounds, bringing with that the possibility of food insecurity for the Gwich’in. During the hearing, Gwich’in Council International Board of Directors member Samuel Alexander stated, “We as Gwich’in see the desire to open up the refuge as an attack on us, and on the Porcupine Caribou Herd on which we depend.” Alexander provided some of the most eloquent testimony of the morning, in stark contrast to the many politicians who struggled to even pronounce the name of his people.

The more northerly living Iñupiat, who traditionally rely on marine mammals like whales and seals for subsistence rather than caribou, tend to support ANWR drilling. In no small part, that is because their native regional corporation, Arctic Slope Regional Corporation, is the only one that owns land within ANWR: some 92,000 surface and subsurface acres in the Coastal Plain, in fact. Those oil-rich lands, held in conjunction with the Kaktovik Iñupiat Corporation, surround the village of Kaktovik.

Since the 1970s, the Iñupiat have profited handsomely from oil and gas development in the North Slope, and their corporations wish to continue expanding their activities into places like ANWR. Matthew Rexford, Tribal Administrator for the Native Village of Kaktovik and president of the Kaktovik Iñupiat Corporation, who testified as a witness during the hearing, explained in his written statement:

“The oil and gas industry supports our communities by providing jobs, business opportunities and infrastructure investments, has built our schools, hospitals, and has moved our people away from third-world living conditions – we refuse to go backward in time.”

Since its incorporation in 1972, Arctic Slope Regional Corporation has become one of America’s 200 biggest private companies and one of Alaska’s largest private landowners. Last year, it generated $2.4 billion in revenues. While ASRC still, in theory, keeps Inupiat interests at the heart of its operations, its size, structure, and activities clearly distinguish it from other indigenous groups. Even though the Gwich’in have a corporation, its operations are nowhere near the level of ASRC, whose subsidiaries won multimillion dollar contracts to support the war in Iraq.

A clash between an indigenous non-profit and an indigenous corporation

Thus, the clash between the Gwich’in and the Iñupiat over ANWR drilling is more than just a disagreement between two indigenous groups. In a way, it is also about one indigenous non-profit organization versus an indigenous corporation. Alexander, the Gwich’in Council International representative, forcefully argued,

“You’re gonna hear Alaska Native Corporation representatives coming up here and talking about responsible development, and I just want to make it clear while I have the time to do such that Alaska Native Corporations are not tribes. They are not tribes. They do not have a traditional language. Their purpose is profit. Our purpose as Gwich’in is to protect our traditional way of life and live that traditional life in an honorable way. (His testimony starts around 1:06 in the archived webcast).

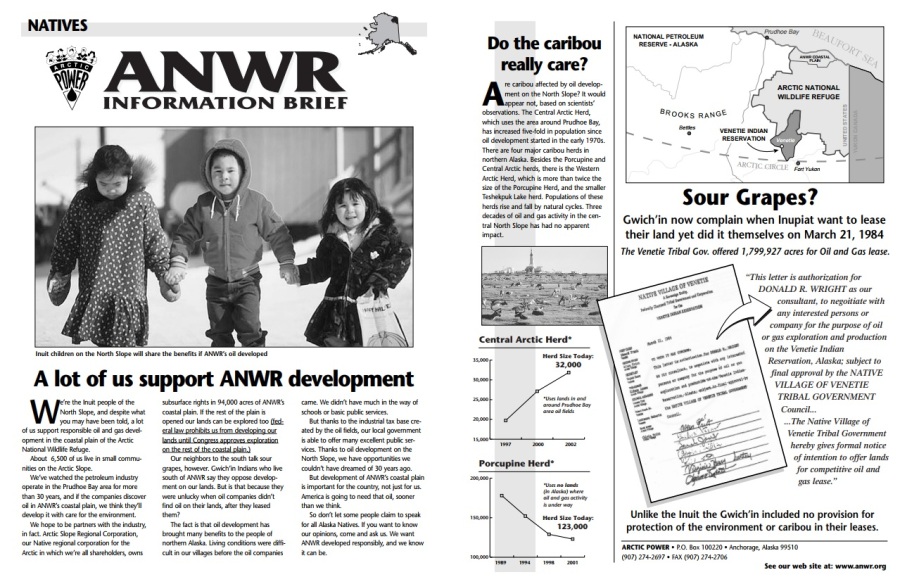

Even the sartorial choices of Alexander and Rexford, the Kaktovik Iñupiat Corporation president, reflected their individual differences. While the Gwich’in representative wore a traditional vest over a shirt and tie, the Iñupiat representative was dressed in a suit. Alexander was representing Gwich’in Council International, a non-profit established in 1999 to represent the interests of Canadian and American Gwich’in at the Arctic Council. Yet the Canadian Gwich’in, too, have their own development corporation, which the Iñupiat and other Alaska politicians have taken pains to point out over the years. The Gwich’in Development Corporation is the majority owner of an oilfield services company, while other Gwich’in tribal organizations officially support development of the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline, a proposed $7 billion pipeline that would export gas from the Canadian Northwest.

Perhaps most ironically, in 1984, Alaska Gwich’in offered nearly 2 million acres for lease to oil companies, but no resources were found. The below undated information brief published by Arctic Power, a non-profit that supports ANWR drilling, sheds light on the seeming hypocrisy of the Gwich’in, who are against drilling in ANWR but pro-drilling on their own lands.

What does it mean to say, “Let us live as Gwich’in”?

What needs to be remembered, however, is that no single indigenous group speaks with a single voice. Just as you would never expect all Californians to be unanimously opposed to oil drilling, the Gwich’in, too, have diverse views, as do the Iñupiat. Caroline Cannon, an Iñupiat leader and former mayor of the village of Point Hope, won a major environmental prize a few years ago for her work in opposing offshore oil drilling. Similarly, some tribal organizations are in favor of the activity while some are against. Alexander clearly opposes ANWR drilling for reasons that may not apply to all Gwich’in, but certainly to some, and which may even hold true for some Iñupiat. Yet both indigenous spokesmen used phrases like “We as Gwich’in” or “our people,” rhetoric which occludes the diversity of views among indigenous communities.

The following statement by Alexander exemplifies this tendency. In contrast to Rexford, who sees a direct link between more oil and better public services, Alexander offered:

“I hear this talk about development all the time. We need to develop this, we need to develop that. What I think we need is a little bit of understanding of the sustainability of the life that we live as Gwich’in, alright? We’re not sitting here asking for anything. We’re not saying we need hospitals, we need schools, we need all these things, we’re not saying, give us money. What we’re saying is, let us live as Gwich’in.”

The real question though is what does it mean to live as Gwich’in, or as Iñupiat, for that matter? It is not simply one thing, nor is it even a simple choice between “traditional” and “modern.” An Inupiat who works in the oil industry, for instance, might use his wages to buy a new motor for his boat to go whaling, or a mother might go to the grocery store to buy eggs and milk to supplement traditional foods.

To wit, Rexford, addressing the committee, explained that the Iñupiat see oil and gas as just one of the many resources that they rely on. In this sense, even oil can be reimagined as a subsistence resource.

“The bowhead whale, caribou, Dall sheep, muskoxen and the fish of the region are a vital food source to the Kaktovik-miut (people). Another of those natural resources is oil and gas – and lots of it. We rely on the bounty of the land and find sustenance within ANWR.”

What counts as a natural resource?

This description of the bounties of the land opens up a philosophical debate into what natural resources are, along with which ones governments should permit indigenous peoples to develop. If indigenous peoples own their land and can, say, hunt caribou or polar bears on it (within certain limits), should they also be allowed to drill for oil?

So far, with ANWR, the U.S. has said no. Rexford lamented,

“Since the mid-1980s, our people have fought unsuccessfully to open our homelands to responsible exploration and development…Kaktovik-miut and the Arctic Iñupiat will not become conservation refugees. We do not approve of efforts to turn our homeland into one giant national park, which literally guarantees us a fate with no economy, no jobs, reduced subsistence, and no hope for the future of our people.”

What this all boils down to is a fight not between two indigenous peoples, but between capitalism and the subsistence economy. I hesitate to even use the phrase “sustainable development” because that concept implies ceaseless growth. Alexander posed a question that illuminates the fundamental debate at the heart of the ANWR clash, which is over whether society needs to keep developing, even if the environment can be somewhat protected. He asked,

“What does economic development actually mean? It’s not a recognition that the subsistence economy is a real thing.”

If we are going to have more and better schools and hospitals and avoid “going backward” or even just remaining in the present, then we do need to keep developing, whether that’s by getting resources out of the ground or generating economic activity in some other way. Even Alexander, who adamantly supports subsistence lifestyles, is a professor at University of Alaska Fairbanks. Like many Gwich’in, he is also a veteran.

What all of this suggests is that indigenous peoples wear many hats, just like everyone else. People, both native and non-native, feel a need to go back to the land from time to time, too, and they probably don’t want it to be spoiled exactly on the lands that are important for them, whether its for subsistence or recreation. During the hearing, U.S. Senator Cory Gardner (R-CO) waxed poetic about his 70-mile backpacking trip with his wife. While he probably wouldn’t want to see pipelines and oil patches stretching across the Rockies in his home state of Colorado during his treks, development – and that includes oil extraction – has to happen somewhere if society is going to keep having new and better things. For many Gwich’in, they don’t want development happening on the calving and grazing lands of their caribou, and some, like Alexander, might be ideologically opposed to the idea of development, full stop. But many people probably do still want some form of progress to continue, including the many – but not all – Iñupiat who want drilling on their homeland, and who feel they have a right to develop it as they see fit.

Traditionalists versus developmentalists

The redrawing of battle lines over ANWR complicates typical notions of fights over development. Armchair readers and activists might think of the fight over ANWR’s future as a black and white debate between environmentalists and Native Americans facing off against profiteering multinational oil companies. As the heated hearing in D.C. elucidated, the story is rather one of Gwich’in traditionalists, who have environmentalists on their side, versus Iñupiat executives and developmentalists, who have Juneau politicians and Texas oilmen on theirs.

What an honest and excellent piece of writing about a complex subject. The conflicting interests of and within the tribes mirror most other questions about whether to develop or leave alone assuming leaving anything alone is even a possibility now.

Thank you for reading, Jessica.

Now that you’re using https://www.cryopolitics.com instead of cryopolitics.wordpress.com, is there a way to subscribe so that I receive a notification when there are new posts?

Hi K.H.,

If you subscribed already, you will still receive email updates. If you haven’t subscribed yet, there’s now a “subscribe” option on the right side of the page. Thanks for reading!