Arctic shipping is not off to a good start this season.

On July 25, the privately owned management company, Omnitrax, announced that it was shutting down the Port of Churchill, giving some 40 workers the dreaded two-week notice. Shipping usually runs from late July to early November, meaning that this year’s shipping season will barely even get started before being drawn to an abrupt close.

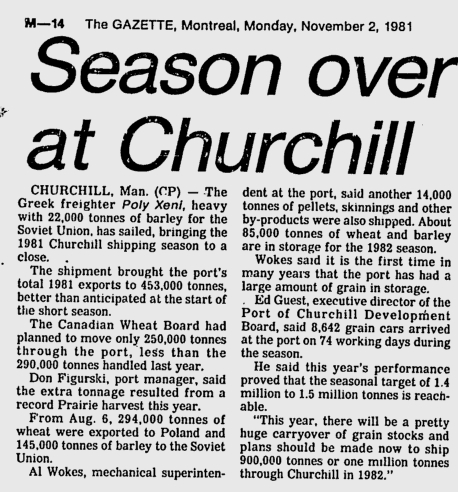

Churchill exports grain, minerals, and timber from Manitoba and Saskatchewan while importing ore, minerals, steel, and petroleum products for markets in Central and Western Canada and the U.S., according to Omnitrax‘s website.

In 1992, building on these little-known but longstanding trade ties, Canada and Russia signed the Arctic Bridge Agreement to promote shipping between Murmansk, a port city in northwest Russia, and Churchill via the Barents and Norwegian Seas and Davis Strait between Greenland and Canada. According to the plan, Murmansk would export mineral and timber products, and Churchill would continue shipping out grain.

That plan never really came to fruition. Today, concentrating on the decidedly unglamorous world of bulk and grain shipments, the Port of Churchill doesn’t rank high on many Arctic cruise itineraries. Most visitors come by rail or air rather than by sea. Located on the southwest shores of Hudson Bay, the town offers one of the closest and most accessible Arctic experiences for the many Canadians who live in central Canada and Ontario. Fluffy white polar bears, spawning, chubby beluga whales, and the colorful northern lights are the main draws for tourists.

At the bottom end of Hudson Bay, however, Churchill is far from the Northwest Passage. As such, it likely won’t benefit from any increase in cruise tourism along the Canadian shipping route. Crystal Cruises’ landmark luxury Arctic voyage this summer, for instance, will call on Uluhaktok (Northwest Territories) and Cambridge Bay and Pond Inlet (Nunavut), but not Churchill, Manitoba.

A micro and macro-level shock

The closure of the Port of Churchill comes as a blow for the local economy. It’s the largest single employer in the town of 800 people, and approximately 50 port employees have received pink slips.

And at a macro level, the port’s shuttering may deliver an even bigger shock to plans to build out Northern Canada’s transportation infrastructure and develop the regional economy. For all the talk of building deepwater ports in Canada’s Arctic from Tuktoyaktuk to Nanisivik it appears that the Port of Churchill, North America’s sole existing deepwater Arctic seaport, is not even viable. Why would companies or the Canadian government want to invest in building additional deepwater ports in the Arctic when they can’t even keep the only operating one afloat?

Still, it will be surprising if the Canadian government lets the port be closed for good. Given its high symbolic status, it’s possible that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government may move to nationalize the port and buy the port back from Omnitrax, one of the largest private railroad and transportation companies in North America. Omnitrax will be able to keep chugging along even with the Port of Churchill’s closure given its continental-wide operations (a map of its ports and railroads is available here), and it has actually only operated the port for fewer than 20 years. Previously, a crown corporation owned by the Canadian government called Ports Canada operated the port. The government also sold the Hudson Bay Rail Line that extends to the Port of Churchill to Omnitrax in 1997.

Re-nationalizing the port may reveal that a great deal of northern infrastructure, and perhaps even Arctic shipping, simply isn’t economically viable in this day and age – even with climate change and longer shipping seasons. On land, thawing permafrost poses problems for the railroad leading up to Churchill. The issue of shifting ground is common throughout much of the Arctic, making intermodal transportation (smoothly integrating shipping, roads, and rail) more complicated than in the South. And at sea, even though there is less ice in places like the Northwest Passage, there isn’t much more demand in northern markets for goods, while growth is better in the more southern reaches of Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

Arctic deepwater ports: a house of cards?

The dismal economic viability of a lot of Arctic infrastructure means that it is important to carefully scrutinize plans such as the recently announced memorandum of understanding signed between the Government of Nunavut and the Kitikmeot Inuit Association (KIA). They wish to construct a 227-kilometer road to a proposed port at Grays Bay in the Northwest Passage. The road could potentially open up a number of mining regions and provide all-weather access to the Northwest Territories’ diamond mines.

Together, the Government of Nunavut and KIA hope to lobby for federal funding to cover three-quarters of the port’s $487 million price tag – over $365 million, in other words. This would be even more money than the $300 million spent on the 140-kilometer highway from Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk, in the Western Arctic. Construction on that road is nearly finished, and locals and government officials alike there are anticipating a deepwater port to follow. Some have even taken to calling the road “the world’s longest boat launch,” suggesting that even if Tuktoyaktuk erodes away into the ocean as is already happening, there may still be a port up there.

But when Arctic shipping appears to be drying up in Canada – first with the bankruptcy of Northern Transportation Limited Company, which provides resupply by barge to communities in Northern Canada, and second with the closure of the Port of Churchill – spending hundreds of millions of dollars on roads to the ocean with no real hope for viable ports in the near future seems foolhardy. Even though the climate is changing, the philosophy, “Build it and they will come,” still doesn’t necessarily apply in the Arctic.

Decades-long concerns

Today, the Port of Churchill only ships two percent of Canada’s grain exports. Todd MacKay, Prairie Director for the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, said it well: “If customers are choosing other ports to ship grain, the reality is that more taxpayer dollars won’t solve the problem.” Throwing more public funds to construct big-ticket roads and ports in the Arctic will not result in Hong Kongs, Singapores, or even Reykjaviks sprouting up from the tundra, no matter the appeal of glossy brochures promoting Northern development.

This has been true even prior to the current blitz by members of the media, governments, and corporations who are heralding a new era in Arctic development thanks to climate change. In 1994, politicians were already worried about the Port of Churchill’s viability and shelling out of money on the Arctic Bridge project between Murmansk and Churchill. The following is a transcript from an oral question period from the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba in 1994 (full transcript available here).

Mr. Daryl Reid (MLA – Transcona, Manitoba): I would like to ask this government: In light of the fact that we have spent taxpayers’ dollars here in the order of several hundreds of thousands of dollars of taxpayers’ dollars on the consultants for this Arctic Bridge agreement, what do we have to show for those hundreds of thousands of dollars that we have spent?

Hon. Albert Driedger (Acting Minister of Highways and Transportation): Mr. Speaker, the initiative was initially taken in terms of trying to see whether we could assist CN, the Port, everybody in terms of doing more trade through the Port of Churchill. That is why the Arctic Bridge concept was developed. The reports have been coming forward. We are still hopeful that there is going to be activity taking place.

The federal minister Axworthy has said that he himself will also be working in that direction to see whether we can get new enhanced business coming through the Port of Churchill.

So it is not a matter that we are trying to keep the Port of Churchill down. We have been and will continue to do everything we can in terms of enhancing it, including the aerospace thing, the national park out there. If we can get some activity going through the Port of Churchill, I think we have a positive thing going.

Over the years, it seems like polar bears are actually the main thing that have kept Churchill’s economy afloat. The development of the local tourism industry, as Ed Struzik detailed in a story for OpenCanada recently, has helped Churchill from being a one-trick pony completely reliant on the port. Now that the port’s future is up in the air, Churchill may turn into a one-trick polar bear.

One comment

What does the sudden closure of Canada's only Arctic deepwater port mean for Arctic shipping?