While many of the movers and shakers in the Arctic world have been attending the Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromsø, Norway this week, I instead attended a more modest affair on the Arctic in Los Angeles: the Hammer Museum’s exhibition of paintings by Canadian artist Lawren Harris (1885–1970), which just wrapped up on Sunday. The show, called “The Idea of North,” displayed works of art from one of his seminal periods. From the 1920s through the early 1930s, Harris concentrated on depicting northern landscapes in a beautiful but ultimately problematic manner.

In Harris’ paintings, clouds, sky, light, and ice appear distinctly geometric and elemental. All interact, but they also retain their specific structures, with stark shadows and sharp lines separating glacier from mountain. Many of his works focus on Lake Superior, yet Harris’ sole trip to the Arctic inspired him with its even bleaker landscapes and monochromatic colors. Near the end of his landscape painting stage, he partook in a two-month journey on board the supply ship S. S. Beothic. The ship sailed through Davis Strait between Greenland and Nunavut, where Harris sketched and later painted two icebergs rising monumentally out of the dark water. The Hammer Museum’s description accompanying the painting notes that in it, “the iceberg has become architecture, a floating classical ruin.”

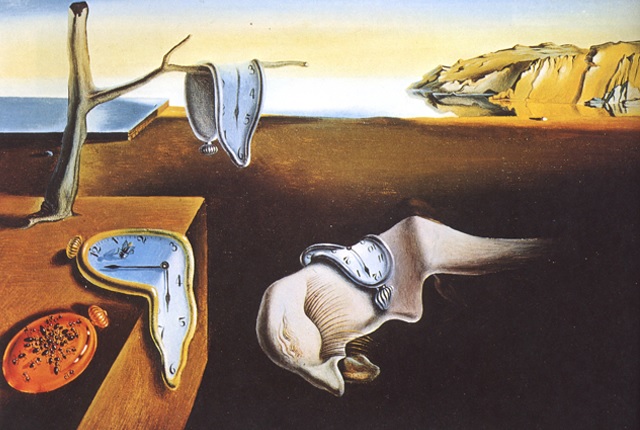

If Harris painted the icebergs today, it might be more appropriate for him to follow a style akin to Dali in his depiction of melting clocks in The Persistence of Memory, which was actually painted just one year after Harris’ Icebergs, David Strait. The ice is melting, and memory may be all we have one day of the ruins of the Arctic.

A misguided ‘Idea of North’

Harris’ work came at a time when Canada’s national identity was still nascent. His depictions of Canada’s landscapes as bleak, cold, and nearly lifeless helped cement Canadians’ idea that their country was a sparsely inhabited northern one.

Yet though Canada certainly has a low population density, its northern regions are far from uninhabited. Indigenous peoples have lived there following the peopling of the Americas via the Bering Strait at least some 13,000 years ago. Harris rarely recognized this in his work. A Hammer Museum description for his painting, Eskimo Tent, Pangnirtung, Baffin Island (1930), explains:

“Unlike his contemporary Rockwell Kent, Lawren Harris did not include figures of or motifs associated with indigenous peoples in his paintings of the Arctic. This panel is a rare exception as it shows the summer tent of an Inuit family perched on the exposed rock of the north shore of Baffin Island…The tent is a rare acknowledgement of indigenous presence by an artist whose unpeopled landscapes reflect a desire to articulate an ethereal sense of isolation. Unfortunately the power of Harris’s vision has led many to imagine the Arctic as an empty and unpopulated land.”

Harris was not the first to imagine his nation as unpopulated in its northern expanses, but his imaginings were clearly influential. Harris was a founder of the Group of Seven, a group of Canadian landscape painters who would perpetuate depictions of their country’s lands as “terra nullius” despite thousands of years of inhabitancy by indigenous peoples.

Later in 1964, Canadian pianist and radio documentary producer Glenn Gould would take the train from Winnipeg to Churchill, on Hudson Bay. The trip inspired him to produce a radio documentary series called “The Solitude Trilogy.” The first and most well-known episode is called “The Idea of North,” from which the Hammer Museum’s exhibit gets its name. In the introduction to the show, Gould remarked, “I’ve remained of necessity an outsider, and the north has remained for me a convenient place to dream about, spin tales about sometimes, and, in the end, avoid.”

Gould was able to conveniently dream about the North in no small part thanks to the shot of industrial steel across the landscape that brought him there: the Hudson Bay Railway to Churchill, which opened in 1929. From the safety and comfort of a train coursing across taiga and tundra, looking out the window and taking in vast landscapes without noticing the people inhabiting them is almost unavoidable for any passenger.

In fact, the idea of traveling across a vast stretch of territory that appears uninhabited has long been part of the sublime attraction of the North. Even today, VIA Rail Canada markets the rail journey to Hudson Bay as having “Beautiful Landscape…The Winnipeg-Churchill train completes the 1,700 kilometre journey (over 1,000 miles!) to the vast subarctic region of Northern Manitoba in two days… See polar bears up close from the safety of ‘Tundra Buggies®’.” Not one mention is made of the possibility to meet local people. The cocooned tourists see landscapes and animals at high-speed with no threat thanks to railways and mechanized vehicles that separate them even from the air outside, unlike kayaks, umiaks, or sled dogs.

Global imaginings of the empty Arctic

Eventually, Harris’ paintings transformed from a “defiantly nationalistic interpretation of the northern landscape towards a universal vision of nature’s spiritual power,” according to the Hammer Museum. Although the artist is still only really known in Canada, the power of his vision of an uninhabited north likely resonates with many of the billions of people who live outside of the Arctic today.

Similarly for the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould, the Library and Archives Canada website explains that “The North was, for Gould, a moral concept as well as an excursion to frozen wastelands.” It’s unclear what the moral concept was to him, but what is striking is that today, many believe humanity has a moral imperative to develop these resource-rich northern “wastelands.” In fact, for many corporations and states whose representatives are this week attending Arctic Frontiers, to not develop their resources would be a regrettable waste. The conference’s theme this year is “Industry and Environment,” and its website observes:

“The Arctic is a global crossroad between commercial and environmental interests. The region holds substantial natural resources and many actors are investigating ways to utilise these for economic gain. Others view the Arctic as a particularly pristine and vulnerable environment and highlight the need to limit industrial development.”

Harris’ paintings, Gould’s radio shows, corporate discourse, and environmental mantras all neglect that the Arctic is also a lived space. It includes more than glaciers, icebergs, and billions of barrels of oil, it is not pristine, and it is not solely a crossroads for shipping between Asia, Europe, and North America. Arctic Frontiers asks, “Envisioning a well-planned, well-governed, and sustainable development in the Arctic, how can improved Arctic stewardship help balance environmental concerns with industrial expansion?” The website does go on to inquire, “What role will existing and emerging technologies play in making industrial development profitable and environmentally friendly, securing a sustainable growth scenario for Arctic communities?” But communities are apparently an afterthought.

In any case, industrial development at current levels and sustainable growth are probably not compatible, especially in areas dependent on natural resource extraction like the Arctic. But the oil majors are proceeding with their projects in the North, contrary to sound science that says Arctic oil must be left in the ground to limit global warming to 2°C. When the inevitable transition to another energy source arises be it twenty, fifty, or a hundred years from now, the oil rigs of the Arctic will, like the whaling ships before them, become floating classical ruins of a past industrial era. But this time, they will have taken the icebergs down with them. The frigid landscapes that Harris’ paintings depict might then appear as distant and otherworldly to a 22nd-century museum-goer as paintings of ancient Rome – which, too, once burned to the ground.

Peter Neill, Director World Ocean Observatory http://www.WorldOceanObservatory.org Eleven years of advocating for the ocean through communications and comprehensive ocean information

The author went into this article on a hobby horse. She did not explore why Harris painted Canada’s north lands from his theosophy mindset. She did not spend time exploring the various phases of his development from the stark more realistic peasant houses that spoke to him with a spirituality his upper crust dwellings apparently lacked. She seemed to be oblivious to his organizational efforts in forming the Group of Seven, and how a fateful visit to a museum in Buffalo that depicted Swedish impressionistic artists painting their northland helped Harris and his associate form their drive to explore the beauty of Canada’s north beginning with Ontario and then branching out. Devoid of this necessary history Mia is a lost soul aimlessly meandering in pictures that do not connect with anything, let alone the spiritual quests of this group of artists for which Harris was the leader in its spiritual depictions. Harris moved from the heavier brush strokes and multi colour early 20s paintings of Algoma, and Lake Superior to more monochromatic but still stunningly eye grabbing, in the colour intensity and variation he found in landscapes that stood out and expressed the divine Creator behind his creation.

Mia is to be pitied for not having the historical interest to ground her in the significance of Canada’s leading artist in both his organizational and artistic skills.

Dear Mr. Weinberger,

Thank you for your constructive criticism. You are correct that I was not aware of the theosophy mindset from which Harris approached Canada’s north. If you have any references you would recommend to learn more about his background, I would certainly be interested in reading them.

Best wishes,

Mia