On a dusty shelf in the library at my university, I came across a volume entitled Marine Transportation and High Arctic Development: Policy Framework and Priorities – Symposium Proceedings. The book had sat untouched for so long that the bar code inside of it no longer even worked, for there wasn’t a catalog entry anymore for it. The blue hardcover book was published in 1979 by the Canadian Arctic Resources Committee (CARC), based in Ottawa, Ontario. CARC still exists today with additional offices in Yellowknife. On its website, the committee describes itself as a “citizens’ organization dedicated to the long-term environmental and social well being of northern Canada and its peoples.” It appears to take a middle-of-the-road approach to Arctic development, as it has supported certain projects such as relocating a mining road to avoid a caribou herd while also in the past accepting donations from organizations like Dome Petroleum, a now defunct Canadian oil company that had pursued exploration in the Canadian Arctic.

1979 seems like a long time ago. The Arctic’s thickest, oldest sea ice still extended almost all the way to the north coast of the Sakha Republic in the Soviet Union, Pierre Trudeau was still prime minister of Canada, Jimmy Carter was president in the U.S., and the oil crisis of 1973 was a recent memory. Weeks after the symposium, the 1979 oil crisis would begin, and in November of that year, a group of Iranian students would take hostage 52 American diplomats and citizens in Tehran.

Yet in reading through the book, which contains all of the speeches and papers given at the symposium held from March 21-23, 1979 in Montebello, Quebec, it quickly becomes apparent how much the Arctic of 1979 seems like the Arctic of 2015. Many of the statements made at the symposium could be uttered verbatim at a contemporary gathering of Arctic-focused scientists, policymakers, businesspeople, and indigenous leaders without anyone blinking an eye. This similarity is all the more surprising given that climate change hardly registered on the agenda in 1979 – the very year satellite records of the Arctic sea ice began – whereas it takes center stage in Arctic matters today.

For instance, François Bregha, of the Canadian Arctic Resources Committee, pronounced,

“In 1979, the Canadian High Arctic stands at the threshold of developments which could forever alter the way in which we think about our North. Some of these developments are well known: offshore drilling in the Beaufort Sea and Davis Strait, the proposed transportation of natural gas reserves by LNG tankers, the exploitation of lead and zinc deposits on Baffin Island. What is not so well known is that they also include the potential shipment of oil through the Northwest Passage on a year-round basis.”

While some of these predictions have materialized, others still stand far off on the horizon four decades later. LNG tankers have indeed transported natural gas in the Northern Sea Route to destinations in East Asia, but drilling in the Beaufort Sea and Davis Strait, large-scale mining on Baffin Island, and oil shipment through the Northwest Passage (NWP) all remain but fantasies. Were Bregha to repeat his statement at a conference in 2015, representatives of many Arctic countries would likely still believe their countries to be standing on the threshold of the very developments he mentioned in 1979.

Ships on the horizon

The energy with which spokespeople trumpeted the NWP in 1979 is strange considering the enthusiasm with which they continue to talk it up. Thirty-six years have gone by, and neither the boosters nor the listeners seem to have tired of discussing how Arctic shipping passages are just around the corner. In the 1979 symposium’s stance, in his keynote address, Professor Max Dunbar of McGill University declared,

“We are concerned at this symposium particularly with the development of the Canadian Arctic sea routes, which may be considered with some confidence to be on the brink of wide openings. The Northwest Passage first came into the language almost 500 years ago. We are now in a technological position to make the final breakthrough which will make the sailing of that passage a normal day-to-day or week-to-week affair.”

Today, politicians and businesspeople posit that climate change is the reason that the Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route are on the brink of becoming bustling shipping routes; previously, people like Professor Dunbar claimed that technological advancements would make it possible. In neither the 1980s nor in the 2000s, however, have climate change or technology brought to life a truly busy Arctic shipping route. The volume of cargo shipped along the Northern Sea Route would peak in 1987, but even then, the tonnage carried paled in comparison to routes like the Suez and Panama Canals.

Oil under the ice

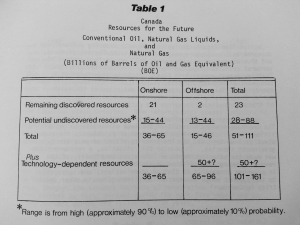

In the transcripts of the symposium proceedings, the topic of Arctic oil appears to generate much excitement. This is similar to the buzzing atmosphere at Arctic conferences in 2008, after the United States Geological Survey released its Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal. (Now, the tone regarding oil extraction is more subdued in part due to the concern over Shell’s abilities in the U.S. and the nosedive that oil prices have taken globally). Oil’s prominence at the 1979 symposium is unsurprising given that drilling had been occurring in the Canadian offshore Arctic since 1972. The papers presented contained charts such as projections of Canada’s “resources for the future” and the transcript of a talk given by G.R. Harrison, a senior vice president at Dome Petroleum, called “The Need for Action-oriented R and D in the Canadian Arctic.” In it, he declared:

“There are two keys to safe and timely development of the Arctic:

1) Vigorous oil and gas exploration

2) Development of an arctic marine technology through an aggressive R and D programme, emphasizing field experimentation and pilot projects.

If we undertake these two initiatives now, we can develop the Arctic in a safe and orderly way, giving proper consideration to the environment and to the northern people. If we wait until energy shortages cause what President Jimmy Carter has described as “the moral equivalent of war,” the process will be hasty and disorganized and could be heedless, particularly of those in our country who may hold different values and convictions from the majority.”

Dome Petroleum would not be the company to “develop the Arctic in a safe and orderly way,” for by 1982, it would be up to its knees in debt. After receiving unprecedented loans from four Canadian banks and government intervention, another Canadian oil company took over Dome Petroleum in 1988 (more on the roots of its demise here). Neither would the Canadian Arctic remain at the frontier of offshore development. In the late 2000s, the consultancy Ernst & Young essentially ranked Canada the least favorable of all five Arctic coastal states in terms of the attractiveness of the country’s Arctic opportunities.

Dome Petroleum would not be the company to “develop the Arctic in a safe and orderly way,” for by 1982, it would be up to its knees in debt. After receiving unprecedented loans from four Canadian banks and government intervention, another Canadian oil company took over Dome Petroleum in 1988 (more on the roots of its demise here). Neither would the Canadian Arctic remain at the frontier of offshore development. In the late 2000s, the consultancy Ernst & Young essentially ranked Canada the least favorable of all five Arctic coastal states in terms of the attractiveness of the country’s Arctic opportunities.

While Dome Petroleum has been relegated to the history books and the Canadian offshore relatively dormant for the time being, oil men and politicians today carry on the company’s tactic of using fear-mongering to champion oil extraction in other parts of the Arctic. Geopolitical insecurities in the Middle East and concerns over energy shortages were cause for concern in 1979, and they remain so today. As Shell’s website conveys, “Developing Arctic resources could be essential to securing energy supplies for the future, but it will mean balancing economic, environmental and social challenges.”

Whether in 1979 or 2015, the Arctic is constantly discussed in the future tense. Rare is the acknowledgement of the past – such as that Dome Petroleum eventually went bust – or of the present, such as the fact that the Canadian Arctic still doesn’t have a university.

A need for higher education

That brings me to a point brought up early on during the symposium in Professor Dunbar’s keynote speech. He remarked,

“It has begun to grow upon me that where the least progress has been made, and where the greatest urgency lies, is in the education of the native peoples of Canada, and especially in the Arctic.”

Thirty-six years later, Canada still does not have an Arctic university. Ironically in 2009, the country’s former governor-general, Michelle Jean, remarked in an interview with the Canadian Press in Clyde River, Nunavut that “Canada is at least 40 years behind” in providing higher education to its northern residents. In other words, Canada has made no progress since Professor Dunbar underscored the urgency of improving northern education at the 1979 symposium. Back then, he attributed the lack of a good education system to an overbearing state. He argued,

“Again the trouble, as elsewhere, seems to have been primarily one of government arrogance. There has been an attitude that assumes that only government – which means the bureaucracy – can organize northern education, as northern science. The Arctic Biological Station at Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue has recently become a celebrated instance of this attitude within the scientific context.”

I could find little about the Arctic Biological Station on the internet save for this document, so perhaps it is now defunct. In any case, Dunbar’s comment about the Arctic Biological Station, which was located just west of Montreal, brings to mind the Canadian High Arctic Research Station (CHARS), which is being built in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s website for CHARS explains that “this station is being built by Canadians to serve the world, and engage Northerners in cutting-edge science and technology.” Once again, the high-minded paternalism of the Canadian government has not abated in forty years, even if other materializations of this attitude like the Arctic Biological Station have. While scientists working at CHARS may engage with indigenous people and knowledge, the express goal of the Canadian government seems to be to impose science and technology from above onto the residents of the Arctic. In four decades, it appears that many government officials in Canada and around the Arctic still have not really learned from previous mistakes. That may be due to the obsession that many in the Arctic have with the future and their disdain for the past. If they only looked back, they would see how the choirs cheering the potential for states, industry, and science to quickly develop the Arctic have been singing a tired refrain for decades.

It wasn’t all fantasy. The lead/zinc on Baffin Island they were referring to was the mine at Nanisivik that had been in production for 2 years already at that point. The mine at Little Cornwallis Island was still 3 years in the future, crude oil shipments from Bent Horn were still 6 years in the future. Development pretty much stopped when the mines got to the end of their productive life at about the same time as the bottom fell out of the market. Bent Horn lurched to a halt when the price of crude wouldn’t go above $15/bbl. It’s not that it never started, it’s that it stopped and never really picked up again.

Thank you for the recognition…Since 1979 the issues don’t change, the “2030 NORTH” conference examines 5 policy papers commissioned by CARC…available on the CARC WEB site…www.carc.org…CARC continues to deal with Arctic issues with an examination of the state of the Arctic Children in Times of Change Project, Cumulative Effects Mapping, and Arctic Sovereignty…all donations gratefully received…