In May 2013, China gained observer status in the Arctic Council, the preeminent intergovernmental organization of the world’s northernmost region. China, along with South Korea, Japan, Singapore, India, and Italy, joined the ranks of existing observer states like the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Spain, to name a few. China’s newfound status does not allow the country any significant powers in the body. The group’s actual decision-makers remain the member states – Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States – all of which possess territory north of the Arctic Circle, and the permanent participants, constituting six indigenous peoples’ organizations. Despite the relative lack of power China has in the Arctic Council, many in the Arctic and elsewhere in the West still perceive a threat from the east to a northern region seen as a place that has always been “theirs.”

A closer examination of history reveals that the Arctic is hardly a frozen, isolated region unchanged since time immemorial. Nor has Asia always been so far removed from it. In 1644, the Manchus invaded Beijing from the north and established the three-century long Qing dynasty. As a Tungusic people, the Manchus trace their roots to Siberia, and prior to that, all the way back to an ancestral homeland in present-day northern Russia. After nearly four centuries, Han Chinese culture has almost completely assimilated Manchus. Many, however, can still be found in northeast China today, especially in Heilongjiang – China’s northernmost province and one that pops up in Chinese officials’ contemporary claims to being a “near-Arctic state”. Manchu, a highly endangered language, is part of the same Tungusic language family as Evenki. This is the tongue spoken by a traditionally reindeer-herding people living across the enormous swath of tundra and taiga stretching from the Arctic Ocean to Manchuria. In this light, China’s links to the Arctic are not just the result of a 21st century race for natural resources. They are more ancient and invisible than that.

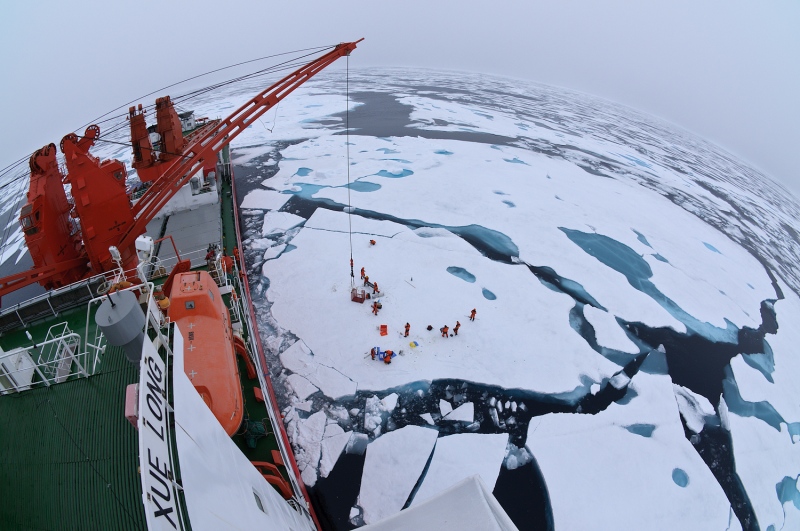

China’s involvement in the Arctic and sub-Arctic is therefore less surprising given the long history of exchanges and encounters between various peoples in northern Eurasia. What is remarkable now though is the scale of Chinese investment across the Arctic. Chinese companies are investing in an iron ore mine in Greenland, offshore oil deposits off Iceland, natural gas development in Arctic Russia, and the construction of homes and schools in Sakha, to name just a few projects.

Of the Arctic countries, Russia has especially welcomed Chinese investment, exemplified by the $400 billion, 30-year gas deal between China National Petroleum Corporation and Gazprom in May 2014. The Kremlin recognizes that Chinese capital is crucial to developing its resource rich eastern region now more than ever due to U.S. and European sanctions. At the same time, many in Moscow fear that severe depopulation in the Russian Far East is turning this peripheral region into a vacuum, opening the door for a Chinese “invasion.” The situation in the Russian Far East is a microcosm for the Arctic, where many northern countries greet potential Chinese investment with equal parts anxiety and excitement.

Fears of Chinese, or more broadly Asian, activity in the extreme latitudes exemplify what Klaus Dodds, a professor of geography at Royal Holloway, has termed “Polar Orientalism.” A recent story in The Financial Times described the takeover of Greenland’s Isua iron ore mine by a privately owned Chinese mining company as “the first Arctic resources project to come under the full ownership of China.” For comparison’s sake, Cairn Energy, an independent Scottish oil and gas company, holds eleven licenses in Greenland with stakes that are close to full ownership, ranging from 87.5% to 92%. But when the company was awarded these licenses, journalists did not express similar concern about Scotland or the United Kingdom owning part of the Arctic.

When considering the activities of the Chinese government and firms in the Arctic today, it is helpful to once again situate them within the longer history of the Middle Kingdom. Whereas the aforementioned Qing dynasty vastly expanded China’s territory through war and conquest, the preceding Ming dynasty spread its influence by encouraging expansive trade networks. Contemporary China draws more parallels with the Ming dynasty’s world of trade, transportation, and exchange rather than the Qing world of territorial expansion. Chinese officials have expressed interest in using the Northern Sea Route (NSR), which follows Russia’s northern coast, as a shipping shortcut between Asia and Europe. This recalls the Ming dynasty’s restoration of the Grand Canal between 1411 and 1415, which improved efficiency of domestic trade. Furthermore, China has no territorial claims to the Arctic. In 2010, China’s former Ambassador to Norway, Tang Guoqiang, remarked at a conference in Tromsø, Norway, “China respects the sovereignty of the Arctic regions of the countries which, in accordance with international law, enjoy sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the Arctic.” Many other Chinese officials have since echoed his statement.

Certainly, Arctic residents have reason to be wary of Chinese investment. The country’s voracious appetite for commodities like minerals, oil, and gas may seem overwhelming at times. As the world’s biggest emitter of carbon dioxide since 2007, there can be no doubt that China is partly responsible for exacerbating Arctic climate change. It also seeks to benefit from this massive environmental shift. State-owned China Ocean Shipping Company, for instance, was the first to send a container ship via the NSR, which is increasingly accessible due to melting sea ice. Although the Arctic shipping route promises to reduce shipping time between Europe and Asia by up to 40 percent, it will not compete with established sea lanes like the Panama Canal any time soon.

The same could be said of other Arctic resources that interest China, like oil and gas: expensive, hard to access, and still relatively unknown entities. Yet China continues to examine these transportation and resource alternatives in the northern latitudes because the country’s policymakers and businesspeople take a long-term view. This is a perspective that, if they are wise, will incorporate the environment, too. For though the Arctic is bountiful, it is also vulnerable to threats much more serious and real than Chinese “invasions.”

***

This post first appeared on March 16, 2015 on the University of Nottingham’s China Policy Institute Blog as part of a special series on China and the Arctic.