At first glance, it might seem odd to compare the Arctic and Central Asia – two regions whose physical geographies are nearly opposites. The former is a largely watery space surrounded by littoral states, while the latter is landlocked. The Arctic Ocean’s political boundaries have yet to be fully delineated, while the countries in Central Asia have generally settled borders (with several notable exceptions, however). Despite these differences in territory and sovereignty, states and corporations commonly frame both regions as “the next frontier” while drawing attention to the vastness and richness of each region. In a seeming geographic paradox, the two regions are described as pristine hinterlands while simultaneously posited as crossroads or “logistic nexuses” that connect European and Asian markets. English professor and Arctic scholar Adriana Craciun writes, “The Arctic is not an uninhabited, timeless waste found on the fringes of the planet – it inhabits a centre.” [2] The Northern Sea Route is excitably touted as a passage to quickly link the markets of Europe and Asia. Likewise, Central Asia has been called a crossroads of the world connecting numerous markets. In a metaphor uniting 2nd century Central Asia with the 21st century circumpolar north, Malte Humpert, founder and executive director of the Arctic Institute, called the Arctic “A New Silk Road for China.”

There is a thus a tendency to paint the Arctic and Central Asia as frontiers that are simultaneously peripheral and central. On the one hand, they are a resource periphery from which industrialized nations can draw oil, gas, and minerals. On the other hand, they are posited as a central nexus for transportation. Yet whether these discourses put the region on the periphery or at the center, in both cases, the landscape is described as a frontier. The deployment of such framings, or “frontier discourses,” are assisted by the fact that both Central Asia and the Arctic are sparsely populated.

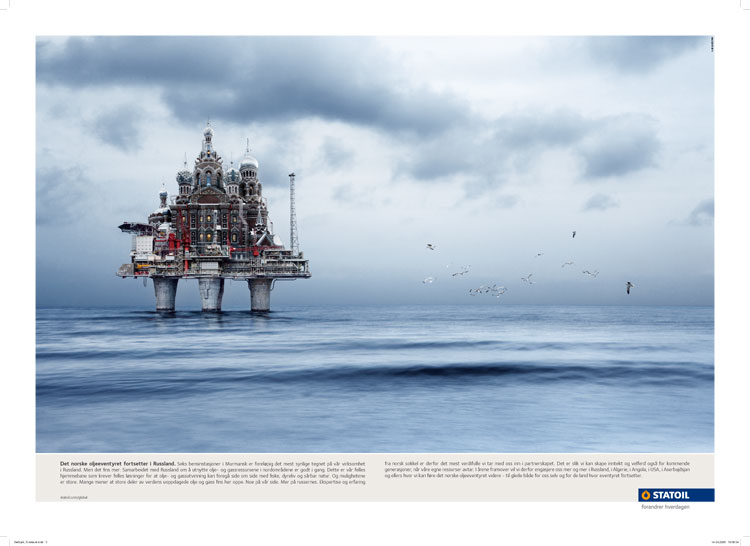

In fact, in descriptions of the Arctic and Central Asia, the landscape is often discursively vacated of its inhabitants. Advertisements feature empty landscapes as opposed to local peoples and wildlife. Companies such as Norway’s Statoil, which had operations in both the Arctic and Central Asia until 2013, project civilization onto the vast periphery in an attempt to familiarize the unfamiliar, to paraphrase the political geographer John Agnew. As described on BLDG BLOG, a Statoil campaign from 2006 superimposed images of classic monuments such as Moscow’s St. Basil’s Cathedral and Rome’s Colosseum onto oil drilling platforms in undisclosed, remote-looking locations at sea and on land. The particularities of the frontiers, which these ads depict as uninhabited expanses, are irrelevant. The message transmitted instead equates resource exploitation with some of civilization’s most celebrated monuments, visually conquering and literally civilizing the nameless, wild frontier.

Amazingly, Shell even goes so far as to include Kazakhstan in its map of Arctic operations. On its website, Shell states that the technology they are developing in Norway “could also be applied to developing Arctic deep-water resources. In 2010 we gained lease blocks in the Baffin Bay area of Greenland. And our experience includes developing ways to meet the challenge of the icy conditions of Kazakhstan,” thereby mentioning the Central Asian republic and remote Arctic locations in a single breath. The Kashagan Field depicted on the map is located in the Caspian Sea, parts of which do tend to freeze in winter. Since technologies and experience are transferable between the Arctic and Central Asia, this actually helps to situate these two regions thousands of miles apart into a single, wider extractive frontier while overlooking the idiosyncracies of each region. A lot is therefore said about technology transfer, but much less is mentioned about how ways of working with, say, indigenous peoples or local residents, are (or are not) shared from place to place.

Andy Brown, Shell’s Upstream International Director, gave a speech last year entitled “Conquering new frontiers together.” Such language puts extractive interests and the landscape in opposition with one another from the get-go. The relationship is one of defeating the elements rather than cooperating with them. It’s also worth noting that the “together” in his speech refers to the oil and gas industry and shipping industry – and not, say, corporations and local people. In his speech, Brown discusses the energy frontiers of Norway, Malaysia, the Gulf of Mexico, West Africa, and predictably, adds, “We can’t talk about new frontiers without mentioning the Arctic.” The single, extractive resource periphery for fossil fuels therefore stretches beyond just the Arctic and Central Asia, which more represent the latest edges into which the frontier has extended, especially in the case of the Arctic. In thinking about how we take resources from the earth, moving away from narratives that emphasize conquest may help us to view nature as more of something we need to work with rather than against – no matter the location.

One comment

Extractive frontiers: The Arctic and Central Asia